History & Culture in Slovenia

Located on the crossroads of Europe, where West meets East and both meet South, Slovenia’s diversity also resonates very strongly with its population of just over 2 million and can be felt on every step.

Influenced by an exceptionally long list of cultures stretching back to prehistoric times, Slovenia is steeped in tradition, with practically every village adding its unique character to the mosaic of the country’s enviable cultural heritage.

When you’re not exploring the wild outdoors, your Slovenia holiday should definitely include visiting the country’s numerous castles, churches, monasteries, museums, galleries, and other places of culture that preserve so well our past, celebrate our present, and envision our future.

History of Slovenia

Slovenia’s history is long, turbulent, colorful, and very rich. The territory of this small, young country has been under the reign of various empires, kingdoms, and states. Numerous tribes have settled here or passed through these lands, attributing greatly to the diverse cultural wealth of present-day Slovenia.

Let us take a short trip back in time to revisit some of Slovenia’s milestones through the ages.

Prehistoric times

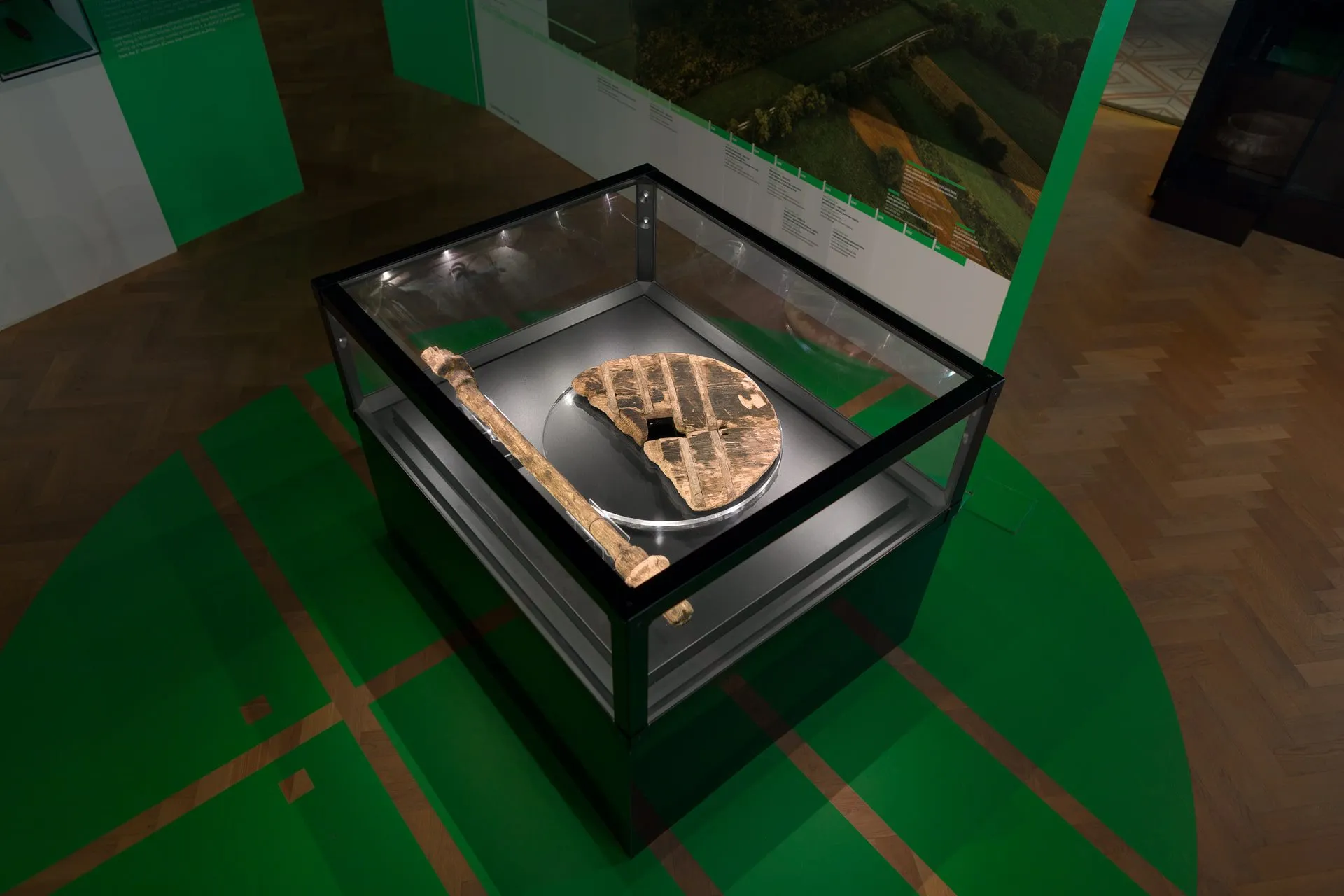

The south side of the Alps has seen human habitation and migration as early as around 250,000 years ago. A 60,000-year-old pierced cave bear bone found in 1995 in Divje Babe cave near Cerkno, which resembles a flute, is possibly the oldest musical instrument ever discovered. Other similar artifacts have been found around former neanderthal dwellings, like a prehistoric needle (30,000 years ago). The Ljubljana Marshes, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is famous for the remains of pile dwellings where the oldest wooden wheel (5,200 years) was discovered.

Between the Bronze and Iron Age, the Urnfield culture saw its peak in Slovenia’s territory, and Archaeological sites, particularly from the Hallstatt period, are scattered all over south-eastern Slovenia, indicating that was soon inhabited by Illyrian and Celtic tribes in the Iron Age.

Illyrians, Celts & Romans

From the 4th to 3rd century BC, predominantly Illyrian tribes were flourishing in this part of the world, and in 250 BC Celts began settling in various regions. Records show that in 221 BC, Romans ventured near the Julian Alps, which saw the first clashes between Romans & Celts in the area.

By 9 BC, the entire area of present-day Slovenia was under Roman rule. It was shared between Venetia et Histria and the Pannonia and Noricum provinces. In 14 AD, Romans established Emona (Ljubljana), which was a strategic trading post, populated mostly by merchants and craftsmen. The oldest town in Slovenia was Poetovio (Ptuj) and Celeia (Celje) received municipal rights as early as 45 AD.

Romans constructed trade and military roads that crisscrossed Slovene territory, fortifying strong trade routes from Italy to Pannonia. During incursions into Italy in the 5th and 6th centuries, invasions by the Huns and Germanic tribes marked the beginning of the end for Roman time Slovenia.

Slavic tribes

In 550 AD, the first wave of Slavs arrived in Slovenia. They migrated from the East and settled near the Alps after the withdrawal of the Lombards (the last Germanic tribe) in 568. The second wave of Slavs (585 AD) saw the cultural & linguistic identity of the local population change forever. It marks the deeply enrooted Slavic culture in this area.

The 7th century then saw long-lasting battles between the Avars and Merovingians. King Samo united the Alpine and Western Slavs against the Avars and Germanic peoples and established what is known as Samo’s Kingdom, the first Slavic realm in this region. After the king’s death in ca. 659, the ancestors of the Slovenes formed the independent duchy of Carantania, present-day Carinthia, and Carniola, later to be called the duchy Carniola.

In fact, Carantania is known as the first independent Slovene (Slavic) principality, which lost its independence in the 8th century and became part of the Frankish Empire under Charlemagne. Although uprisings against the Avars continued, the local pagan Slavs soon accepted the Christian faith.

Middle Ages

Three decades after Christianity established its firm roots in this subalpine region, the Carantanians were incorporated into the Carolingian Empire. Following the anti-Frankish rebellion of Liudewit at the beginning of the 9th century, the Franks removed the Carantanian princes and replaced them with their own dukes. This was a major turning point in Slovenia’s history, as the Frankish feudal system reached the Slovene territory and foreign rule, which became a constant throughout Slovene history, sprang roots.

After Emperor Otto I defeated the Magyars in 955, the Slovene territory was divided into several border regions of the Holy Roman Empire. Carantania, already the most important, was elevated into the Duchy of Carinthia in 976, and by the 11th century, the Germanization of what is now Lower Austria isolated the Slovene inhabitants from the other western Slavs. Thus, the Slavs of Carantania and Carniola gradually merged into an independent Carantanian-Carniolans-Slovene ethnic group.

In the year 1000, the Freising Manuscripts appeared which are the oldest documents written in what was to become the Slovene language. However, throughout Slovenia’s history, the local (native) language played second fiddle to German and by the 12th century, Slovene towns received their German names: Ljubljana (Laibach), Celje (Cylie), and Maribor (Marchburch).

Between the 11th and 14th centuries, these lands were ruled over by various feudal families, like the Dukes of Spannheim, the Counts of Gorizia, the Counts of Celje, and the House of Habsburg. It was during this time that German colonization significantly diminished the still forming Slovene language.

The Carantanian dynasty was taken over by Bohemian king Ottokar II in the 13th century and the Habsburgs establish their rule over a great majority of the land and remain a force to be reckoned with right up until the early 20th century. By the 15th century, the most prominent nobles, the Counts of Celje, rose to Princes of the Holy Roman Empire in 1436 and Ljubljana became the seat of a diocese.

At the end of the Middle Ages, the Turkish raids caused great economic and social hardships in the area of present-day Slovenia, and in 1515, a peasant revolt spread across almost the entire Slovene territory. This was just the start of the troubles, for in 1572 and 1573 huge Croatian-Slovenian peasant revolts spread throughout the wider region. Such bloody uprisings continued throughout the 17th century.

But it wasn’t just doom and gloom. Numerous positive breakthroughs happened, like the first printed Slovenian book in 1550, the Slovenian translation of the Bible in 1583, the founding of the scholarly society Academia operosorum Labacensis in Ljubljana in 1693, and in 1701, the Philharmonic Society was established in Ljubljana, which was one of the oldest in the world.

Early modern period

After the dissolution of the Republic of Venice in 1797, Slovenia was swallowed up by the Austrian Empire, and before too long, Napoleon’s armies marched in and Slovenia’s territory fell under the French-administered Illyrian provinces.

Industrialization was accompanied by the construction of the first railway in 1838. This period saw massive migrations due to very limited opportunities, so between 1880 and 1910 around 300,000 Slovenes emigrated abroad, mainly to the US, South America (Argentina), Germany, Egypt, and other cities in Austria-Hungary.

Despite these turbulent times, the 19th century saw a revival of Slovene culture and language, and the idea of cultural and political autonomy flourished. The concept of a United Slovenia was first realized during the revolutions of 1848, unifying the majority of Slovenian parties and political movements in Austria-Hungary at the time.

In 1851, the first Slovenian publisher was established in Klagenfurt and books started being published in Slovenian. During this period, the ideology promoting the unity of all South Slavs became a popular response to Pan-German nationalism and Italian irredentism. But just as the spring of Balkan and Slovene autonomy began to bloom, a horrific conflict engulfed Europe, putting everything on hold.

World War I

WWI brought exceptionally heavy casualties to Slovenia, particularly the twelve Battles of the Isonzo Front (in the mountains near the Soča River), which took place along today’s western border with Italy. Hundreds of thousands of conscripts were drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army and over 30,000 fell.

Slovenes living in the Princely County of Gorizia and Gradisca were resettled in their thousands in refugee camps in Italy and Austria. Following the Treaty of Rapallo in 1920, roughly 327,000 Slovenes were displaced in Italy, and after the fascists took power, these were subjected to violent Italianization. Yet again, mass emigration of Slovenes from the Slovene Littoral and Trieste began. The southwestern region of Slovenia was involved in passive and armed anti-fascist resistance throughout this time.

Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Kingdom of Yugoslavia)

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was proclaimed at Congress Square in Ljubljana on 20 October 1918. The Slovene People’s Party demanded the creation of a semi-independent South Slavic state under Habsburg rule.

Most Slovene political parties backed this decision, and the widespread Declaration Movement ensued. The Austrians denounced this movement, but following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire post-WWI, the National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs took power in Zagreb on 6 October 1918. Not long after, independence was declared in Ljubljana as well as by the Croatian parliament, and the new State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs was born.

On 1 December 1918, this State merged with Serbia, becoming part of the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and in 1929, it was renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Even back then, Slovenia was the most industrialized and westernized state and became the center of industrial production and economic development.

This interwar period brought prosperity to Slovenia. Right before WWII broke out, the National Academy of Sciences and Arts was established in Ljubljana in 1937 – another milestone on Slovenia’s road to becoming a modern, academically advanced north-Balkan state.

World War II

Slovenia was the only European nation to be fully annexed by both Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy during World War II. Axis forces invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941 and proclaimed victory in a matter of weeks. South of the country, including Ljubljana, was annexed to Italy, while the Nazis reigned over the rest.

Ethnic cleansing was planned, which involved resettling, expelling or eliminating the local Slovene population. Around 40,000 Slovene men were drafted to the German Army and sent to the Eastern Front. The Slovene language was banned from formal education and its use in public life was restricted. In response to the occupation and slaughter of thousands, the Slovenian National Liberation Front was organized.

Slovene Partisan units acted as part of the Yugoslav Partisan armies led by the Communist leader Josip Broz Tito. Following four years of guerrilla warfare, thousands of deaths in the field and in Italian and German concentration camps, as well as a grave division between the locals drafted by the Nazis (Home Guard) and those who rebelled, Yugoslavia was liberated by the partisan resistance in 1945.

It was the birth of the socialist federation known as the People’s Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Slovenia joined the federation as a constituent republic under its pro-Communist leadership.

Socialism

Due to the Tito–Stalin split in 1948, economic, social, and personal freedoms in Slovenia were held to a much higher standard compared to other Eastern Bloc countries.

Gradual economic liberalization, known as workers self-management, was introduced by the Slovene Marxist theoretician and Communist leader Edvard Kardelj. Tito’s socialism came at a price, and suspected opponents of the Party’s policy were persecuted and thousands were sent to the Goli otok Island, a prison camp in the northern Adriatic.

Throughout the period of Yugoslavia, Slovenia remained the most economically advanced state and enjoyed relatively broad autonomy and its annual production value was estimated at 2.5 times greater than that of its sister republics.

The socialist regime was mainly opposed by intellectual and literary circles, which became especially vocal following Marshal Tito’s passing in 1980. Political and social disputes escalated during the 80s and the death of Yugoslavia was imminent.

Independence and democracy

In 1987, a forethinking group of intellectuals demanded Slovene independence, triggering a democratic movement that began eroding socialism, and in September 1989, several constitutional amendments were passed to introduce parliamentary democracy.

In April 1990, the first democratic election in Slovenia took place and the democratic movement emerged victorious. On 23 December 1990, over 88% of the electorate voted for a sovereign and independent Slovenia, and on 25 June 1991, Slovenia officially declared independence.

A Ten-Day War with Yugoslavia followed, but by the end of July, the last soldiers of the Yugoslav Army based in Slovenia left the country. In December of that same year, a new constitution was adopted and the wheels of democratization were set in motion.

Slovenia joined the European Union and NATO in 2004. Slovenia was also the first transition country to join the Eurozone and entered the Schengen Area on 1 January 2007. It was the first post-Communist country to hold the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in 2008.

Slovenian Culture

Slovenia has an astonishingly diverse and exceptionally affluent cultural heritage, which is closely connected to its unique historic and geographical character. Countless castles, colorful architecture, ancient towns and villages, saltpans, traditional beehive panels, captivating artistic creations, customs, gastronomy – all these and much more make up Slovenia’s appeal as a cultural destination.

The language and other aspects of Slovenian culture are largely influenced by Germanic, East and South Slavic, and Mediterranean traditions.

As mentioned in the History of Slovenia segment, language is the cornerstone of Slovenia’s national identity and is inseparably intertwined with its culture. From the days of Protestantism with the first printed Slovene-language books Katekizem (Catechism) and Abecednik (Elementary Reader), written by Primož Trubar in 1550, literary language gradually flourished and gave rise to an enviable list of great writers, poets, storytellers and the likes. Even the Day of Culture, celebrated on 8 February, commemorates the passing of Slovenia’s foremost romantic poet, France Prešeren.

Visitors to Slovenia have ample opportunity to experience the authenticity of the local culture at numerous events, institutions, and organizations in the form of museums, galleries, theatres, etc.

For Slovenes, culture truly is of high importance and this passion for preserving folklore traditions and customs is evident in the country’s biggest towns as well as the smallest settlements.

A staggering one fifth of Slovenia’s population regularly attends cultural events. To a large extent, the state supports the nation’s network of institutions and finances a big portion of programs, activities, and projects in the field of national and international cultural cooperation, including that of the Italian and Hungarian minorities in Slovenia and Slovenes living abroad.

The largest museums are located in the capital Ljubljana and include the National Museum of Slovenia and the Museum of Contemporary History of Slovenia. Then there are specialized museums (ethnographic, technical, natural science) and other regional museums found all over the country. Perhaps the most notable is the Kobarid Museum, which was awarded the Best European Museum Prize.

However, numerous types of movable cultural heritage and open-air museums can be found in every region of the country. These are a fantastic way of discovering area-specific Slovene culture. Not to mention the large networks of educational paths that run through the Slovenian wilderness.

The arts in their various subcategories can be enjoyed in a number of excellent venues, like the Slovenian Philharmonic, one of the oldest in Europe, or the Ljubljana Opera House, which has recently been freshly renovated.

Cultural events, in general, are extremely popular and well-organized in Slovenia. The Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts, the annual Ljubljana Summer Festival, Festival Lent in Maribor, the Liffe film festival, the Exodos Festival of Dance Arts in Ljubljana, the Ana Desetnica street theatre, the PEN Writers’ Meeting in Bled, the Vilenica Writers’ Meeting in Sežana, and the Biennial of Industrial Design, to list just a few. Cankarjev Dom and Križanke are also venues worth visiting when in search of musical or dance performances.

As for architecture, wonderfully preserved old town centers of Piran, Ptuj, Škofja Loka, Kranj, Kamnik, Ljubljana, etc. present a very colorful assortment of styles stretching through all different periods like Gothic and Baroque. This is very evident in Churches across the country. The most famous examples of this cultural heritage are the church at Sveta gora near Ptuj, and the lovely monasteries Žiče, Stična, and Pleterje. In Ljubljana, creations of the world-famous architect, Jože Plečnik, can be found decorating great portions of the centre.

People

Slovenes or Slovenians, are a friendly, hospitable bunch of subalpine Slavs with a gene pool as diverse as their natural and cultural heritage. Slovenians are a humble and hospitable yet very driven, hard-working tribe with a great love for life, a sense of humor, and the unreserved willingness to lend a helping hand.

They are a very sporty nation, which is evident from the multitude of outdoor activities performed and an unbelievably long list of sports achievements in both winter and summer disciplines. Besides a bunch of incredible athletes, Slovenia has also produced hundreds of famous scientists, inventors, artists, architects, authors, chefs, and other prominent citizens.

Not bad for a country of two million, right?

Towns & Villages

Slovenia doesn’t have huge metropolises. In fact, the capital city of Ljubljana is the biggest, with a population of only 280,000. However, every town is very unique and definitely worth a stroll around.

The blend of various types of architecture, from baroque to modern, gives Slovenian towns soul and character. Villages dotting the countryside are as colorful as their surroundings.

Most places around Slovenia greet you with a healthy mixture of traditional and modernity. Riversides and streets are lined with lovely cafes and restaurants. Town centers have plenty of modern shops, and marketplaces, and offer services of every kind.

If you want to explore the history and culture of Slovenia in person, book one of our cultural holidays.

Only the Best

Expert Local Guides

100% Made in Slovenia

Trusted by Many

Similar know-before-you-go